Examining performance related information of your spark application via spark UI

Important Warning: This post was written a long time ago, and its contents and code may be outdated or no longer aligned with current industry standards. Please proceed with caution. :-)

- Intro

- Application event timeline

- Jobs

- Job details

- Stage details

- The main course - Understanding SQL tab

Intro

Debugging and improving spark performance bottlenecks isn’t a straightforward task most of the time. Performance issues can arise from easy to detect bottlenecks such as wasteful UDFs or issues in the executors, or a more illusive problems such as estimated metrics of input size in SQL plan being very inaccurate.

Luckily, we have spark UI to aid us, but one must know where to look and how to look at the generic data provided by spark UI to find potential issues in his spark application.

In this post I’ll try to point to the parts of spark UI which might display information specifically relevant for various performance issue we might encounter in a spark application.

I always prefer to use examples, so for this post I’ve written a simple application which performs tasks we’ll usually encounter in spark applications, and deliberately causes some common performances issues.

This app will be:

- Reading Data

- Doing Wide Transformation

- Doing Narrow Transformation

- Causing shuffle read and writes

- Causing data spill

- Causing unevenly distributed workload

- Saving Data

I’ve written it in pyspark, but the idea would’ve remained the same even if it was written in scala or java.

We have 2 parquet files,

cities - Containing skewed and duplicate data about world cities and countries:

+--------------------+------+

| country| count|

+--------------------+------+

| Russia|210355|

| Malaysia| 25806|

| France| 633|

| United States|531703|

| China| 799|

| Nigeria| 45254|

| Spain| 569|citizens - Containing citizens count per city.

| name|citizens| country|

......................................

| New York | 8467513 | United States|

| Moscow | 1700000 | Russia |

| Madrid | 600000 | Spain |

......................................Both of the files saved in parquet format and partitioned by the country field.

And we have the following self-explanatory app:

# Read files into a dataframe

from pyspark.sql.functions import upper, col, floor, spark_partition_id

cities = spark.read.format("parquet").load("/folder/cities")

citizens = spark.read.format("parquet").load("/folder/citizens")

# Join cities info with citizens info

cities_full_info = cities.join(citizens, ["name", "country"])

# Repartition into too few partitions

cities_full_info = cities_full_info.repartition(2)

# Add citizens growth estimation for next year

cities_full_info = cities_full_info.withColumn('citizens_next_year', floor(col("citizens")*1.1))

# Write the joined data back to parquet

cities_full_info.write.format("parquet").mode("overwrite").save("cities_full_info")Let’s assume our real production app is not as simple as the example, and no one provided us with a list of issues it will cause. The only thing we know is that it runs slow, and we need to debug it. What are the steps, and at which specific data in spark UI should we look to detect potential performance bottlenecks?

Application event timeline

First, make sure all the executors you expect to participate are added to the application. If not, it might indicate an infrastructure issue, meaning you’re running on less resources than expected.

Jobs

Next, it might be a good idea to get a high level understanding of costly jobs in your app.

You can scroll down to completed (or running) jobs and checkout the duration column to understand which jobs taking longer than expected.

Job details

In the job details page, we get some useful information.

Associated SQL query

We will examine SQL tab later, but if you were using Datasets or DataFrames (which you probably are), you can examine the physical and logical plans of the SQL query by clicking on the associated query ID.

We will get into the details of this later.

Stages

Each job has 1 or more stages, and in the stage summary you can see which one of the stages might be a bottleneck. In our example we have only 1 stage, so we will explore it:

Stage details

In stage details we can see aggregated and per-executor metrics of the stage.

Event timeline

An important thing we might want to examine is that the workload is distributed evenly among the workers. Which in our case we can see is not the case in this particular stage:

We can compare it to a “healthy” work distribution in the read phase of our app, which looks like this:

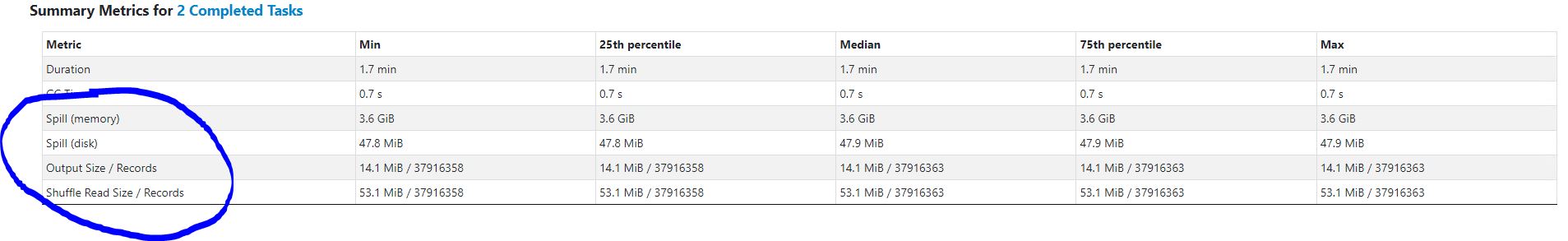

Summary metrics

In the summary metrics you can see summarized stats of all the tasks, but two indicators are specifically important.

Data spills and Shuffle read or write.

These are extremely costly operations, and we need to understand whether we can improve or get rid of it all together.

Tasks breakdown

In the task breakdown, we may examine metrics per task and per executor to get a clearer picture.

But we also have additional information which might be useful for understanding potential slowness - that is the data locality level,

data locality indicates data access latency.

Possible values will be:

- PROCESS_LOCAL - data co-located with the code in the same JVM

- NODE_LOCAL - data located on the same node

- NO_PREF - data with no preference for locality

- RACK_LOCAL - data on the same rack but on a different server

- ANY - Data located on other racks

The main course - Understanding SQL tab

In my opinion this is the most important part to understand since it gives us a clear picture of the application flow,

how much data was moved, how it was moved, which functionality was executed and how long any of them took.

Before examining the logical and physical plan of our application, make sure to toggle on the

Show the Stage ID and Task ID that corresponds to the max metric checkbox, this will help us to correlate parts of the plan

to bottlenecks we saw in the jobs and stages details.

Scanning Parquet

First, we can see the Scan parquet stage which show information about our file structure in HDFS and how long it took the application to

obtain it (Listing leaf and files job).

We can see the number of partitions and files read, both stating 244 - which makes sense since our data was partitioned by country

with a single parquet file per partition:

We can see how long it took to complete the scan (1.2s, 5.6s) and number of output rows. If we hover over this stage we can see additional info such as the directory, schema, and filters that were pushed:

WholeStageCodeGen - fuse of multiple operators

WholeStageCodegen fuses multiple operators together into a single Java function that is aimed at improving execution performance. It collapses a query into a single optimized function that eliminates virtual function calls and leverages CPU registers for intermediate data. In our case, we can see that fuse of 3 different functions into a single WholeStageCodegen:

ColumnarToRow- which generates spark data frame from parquetFilter- which was pushed on thenamecolumn by spark due to the join that will come nextBroadcatHashJoin- which joinscitizensandcitiesdata together (via broadcast due to the relatively small data size)

In both Filter and BroadcastHashJoin we can conveniently see the number of output rows after a specific operator applied.

Next, we will see the Project operator, which simply represents what columns will be selected.

In our case, we will see the product of the join between the 2 dataframes:

Exchange

Next, we will see an exchange in the plan which was caused by our repartition command.

If we hover over the box, we can see the partition method that was used (round-robin). We can also see the total data size, number of partitions, records and various other metrics.

An important thing to notice here (and in the previous step of BroadcastHashJoin) is the number of output rows of the join.

If the number of the output rows is disproportional or doesn’t make sense from your understanding of the data, it might indicate that

there’s something wrong with your data, such as unexpected duplicates in the join column, or your assumptions about the data are incorrect.

Narrow transformation

Here you can see a WholeStageCodegen generated for our citizen multiplication command.

Please note that the duration we see in the WholeStageCodegen (1.3m, see image below) is combining the execution of the repartition command and the column value manipulation.

If we were to remove the repartition command, the column value manipulation would’ve moved to the top WholeStageCodegen function alongside the filter and the broadcast join.

Saving the output

In the end, we see InsertIntoHadoopFsRelationCommand, which representing the writing of the output back to parquet.

Among a lot of interesting metrics, there are few which are performance significant:

- Number of output rows & data size - this is kind of self-explanatory.

- Number of written files - this is important to notice, since constantly creating a lot of small files might impact the performance of whatever reads your data. A good file size will be 512MiB or 1GiB.