Debugging memory leaks: When the famous 3 snapshot technique can cost you days of development

Important Warning: This post was written a long time ago, and its contents and code may be outdated or no longer aligned with current industry standards. Please proceed with caution. :-)

- Intro

- What’s the possible problem with only 3 snapshots?

- Example

- Wait, what? We have objects that aren’t browser’s internals still allocated in snapshot #3. Do we have a leak?

- But that’s easy, i know i need to ignore those object. I’ll just look for something relevant

- So, what can we do?

- But what good it’ll make to take 5 (or even 7) and not 3?

- What about one-time leaks?

Intro

Pretty much every second article about debugging memory leaks demonstrates the great 3 snapshot technique introduced by the GMail team and which was used to debug heavy memory leaks in GMail. While there’s no doubt about it being a great idea, it seems that not many mention the possible problem that may occur if you rely on only 3 snapshots without understanding 100% of your framework, vendor libraries and internals of JavaScript. You might say that one must actually understand and know every line of code in a project he is working on, and it surely an admirable statement, but not really practical in the real world for medium+ sized applications. Just for some proportions: one of the world most famous UI libraries, Kendo, is 166,000 line of codes.

What’s the possible problem with only 3 snapshots?

Well, basically, that snapshot 3 may send you barking at the wrong tree for days. The 3 snapshot technique suggest that objects allocated between snapshots #1 and #2 and still exists in snapshot #3 might be leaking, which is not true in many cases, cases like singleton implementations, services, factories (a nice example will be Angular on-demand instantiation), some of native JS interfaces and basically everything that instantiated between #1 and #2 and have all the rights to keep on living in snapshot #3.

Example

Let’s take a simple code sample where we have 2 buttons, one add items to array and the other removes them. The array lives in a singleton which is instantiated only on demand, but after it was instantiated once, he keeps on living as a global. (I know, globals are the devils work, but bare with me for the sake of the example).

singelton.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>Memory Test</title>

</head>

<body>

<button id="addData">addData</button>

<button id="removeData">removeData</button>

<script src="singleton.js"></script>

</body>

</html>singleton.js

I’ve explicitly named the public/private for retainers differentiation ease.

var myDataLayer = null;

document.getElementById("addData").addEventListener("click", addData);

document.getElementById("removeData").addEventListener("click", removeData);

function getSingleton() {

if (myDataLayer) return myDataLayer;

myDataLayer = (function() {

var instance;

function init() {

var privateDataArray = [], i;

function privateAddToData(numOfItems) {

for (i=0; i<=numOfItems; i++) {

privateDataArray.push(Math.random());

}

}

function privateEmptyData() {

privateDataArray.length = 0;

}

return {

publicAddToData: privateAddToData,

publicEmptyData: privateEmptyData

};

}

return {

getInstance: function () {

if ( !instance ) {

instance = init();

}

return instance;

}

};

})();

return myDataLayer;

}

function addData() {

getSingleton().getInstance().publicAddToData(100000);

}

function removeData() {

getSingleton().getInstance().publicEmptyData();

}Ok so we have this tiny app and we want to make sure we haven’t created any memory leaks, let’s use the 3 snapshot technique (please make sure to test it in incognito and disable all active extensions):

- Open the app and take the snapshot in our “healthy” mode

- Now click on addData and take another snapshot

- After this, click on removeData and take another snapshot

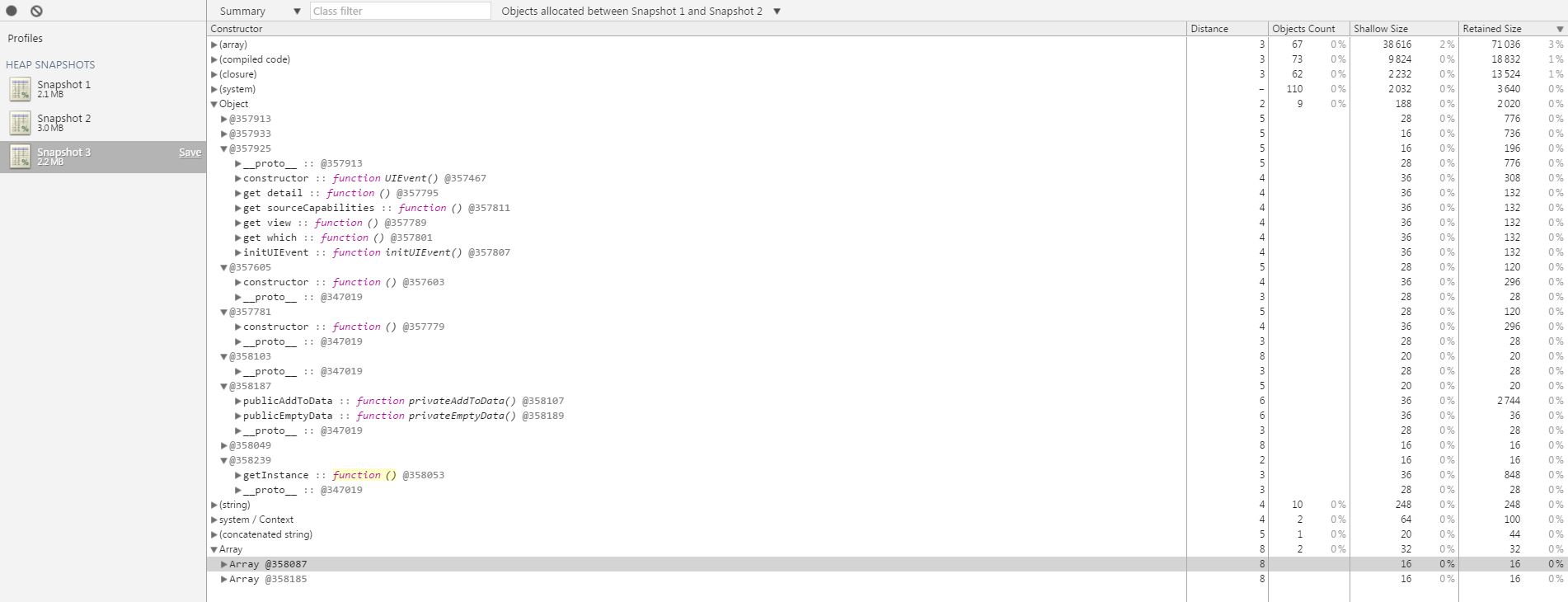

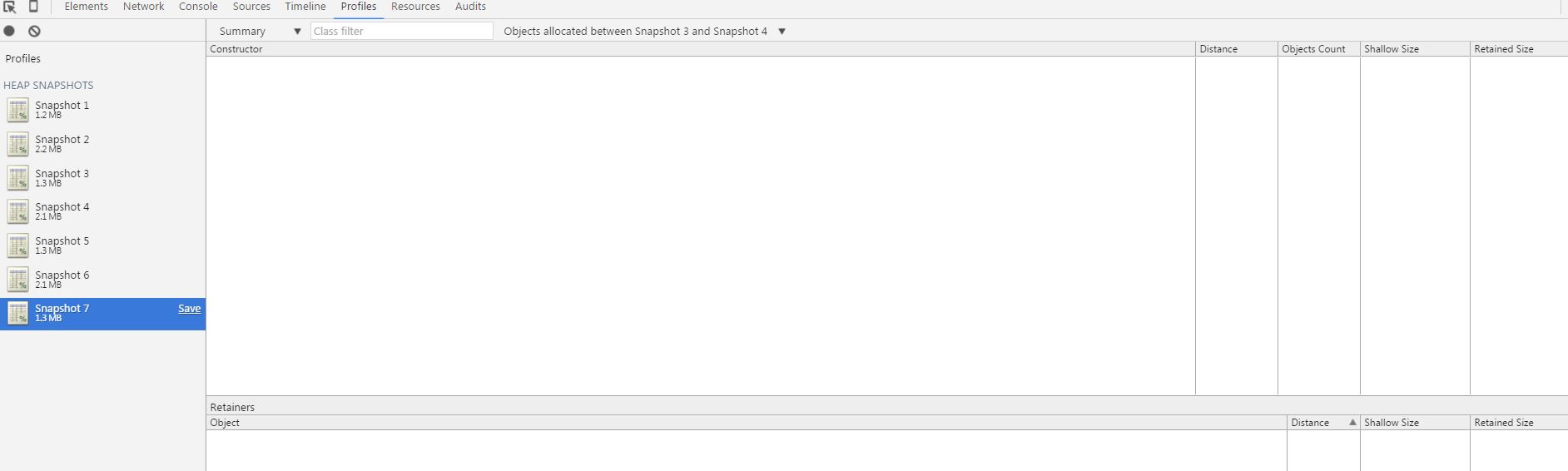

- Next, in snapshot #3, click on Summary and then filter only Objects allocated between Snapshot #1 and Snapshot #2

We will see something like this:

Wait, what? We have objects that aren’t browser’s internals still allocated in snapshot #3. Do we have a leak?

Well, no. As you can see, those objects and arrays related to the singleton we instantiated and to JavaScript’s UI Event and MouseEvent interfaces. All of them logically supposed to live in the 3rd snapshot. The singleton because it’s a global, and the JS Native objects because we still have an active listener (those objects created when the actual click performed, that’s why it’s displaying as objects allocated between snapshot #1 and #2). So yes, we have objects in the 3rd snapshot, but they are not leaking

But that’s easy, i know i need to ignore those object. I’ll just look for something relevant

In this tiny app you may easily find what is relevant and what is not, but if you’re debugging a medium+ application with multiple vendor libraries and complicated business logic, you may waste a lot of time chasing down irrelevant retainers.

So, what can we do?

Consider this: when you have a memory leak in a set of actions (a flow), repeating this action several times will result in a positive linear graph in the JS heap or DOM count (or both). In simple words, in most cases the graph will keep going up as long you’ll keep doing the same action that is causing the leak (i’ll write about a single leak which won’t result in a linear leak in a few moments). Meaning that objects leaked in snapshot #3, will be kept in all following snapshots, and additional memory will be allocated on top of what was in #3. So if you have a linear leak, you may take 5 snapshots and in snapshot #5 compare snapshots #3 and #4 and discover similar types of objects as you discovered in #1 and #2.

For example:

If in snapshot #3, you are viewing objects allocated between #1 and #2, and you see something like:

leakedObject @1

(@ is the location in memory),

then in snapshot #5, where you’ll be comparing objects that were allocated between #3 and #4, you’ll see something like:

leakedObject @2

Meaning, the same object type, leaked twice and created linear leak. If you remove the filter completely and view everything existing in snapshot #5, you will see

leakedObject @1

leakedObject @2

But what good it’ll make to take 5 (or even 7) and not 3?

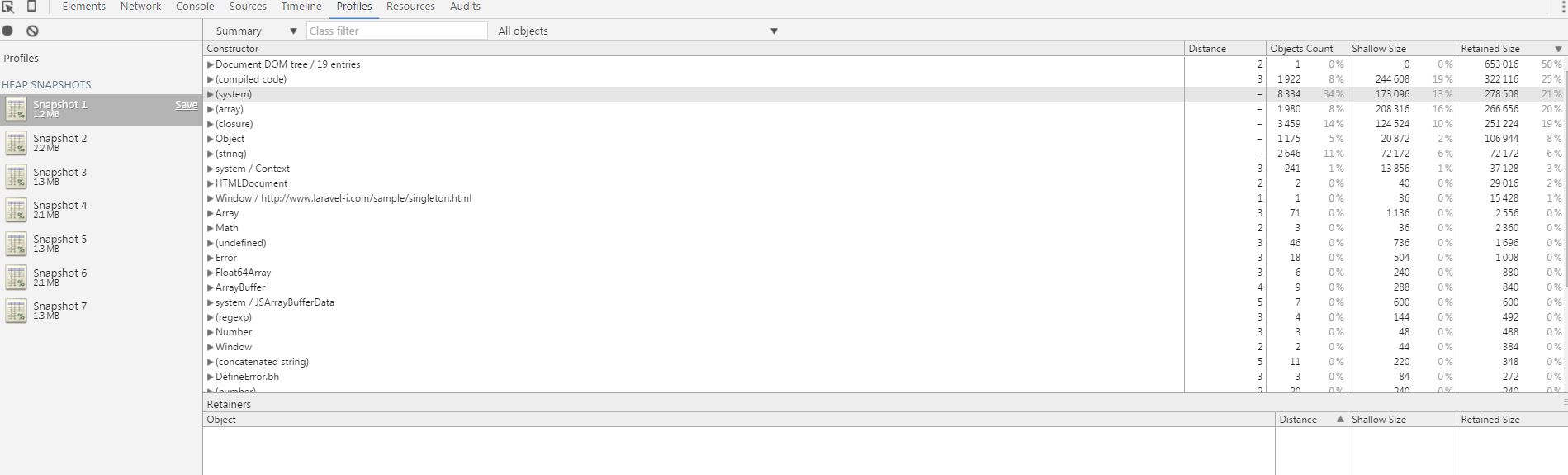

Let’s get back to our tiny app, and repeat the snapshots process, but now we’ll make 7 snapshots and not 3. Repeat those actions (don’t forget incognito to disable all of the extensions):

- Take a snapshot #1 before we begin

- Click on add data, take snapshot #2

- Click on remove data, take snapshot #3

- Click on add data, take snapshot #4

- Click on remove data, take snapshot #5

- Click on add data, take snapshot #6

- Click on remove data, take snapshot #7

You’ll see something like this:

Next, if you’ll go to snapshot #3 and compare between #1 and #2, you’ll see something like this:

As you can see, we have allocated Objects and an increase of 100kb in memory, which in a case you are not 100% familiar with 100% of the app, would’ve make you think you have a leak.

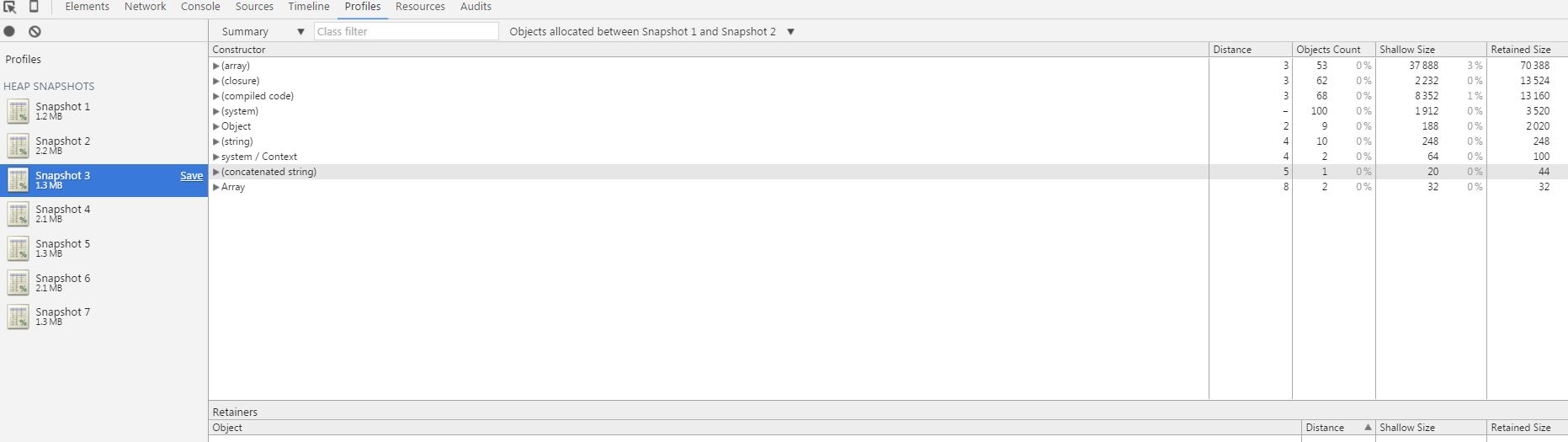

Now lets go to snapshot #5 and there compare between snapshots #3 and #4:

you’ll see 2 things:

- No more increase in memory between #3 and #5.

- No more allocated objects that still living in snapshot #5 (objects wrapped in brackets are browsers internals, we ignore them).

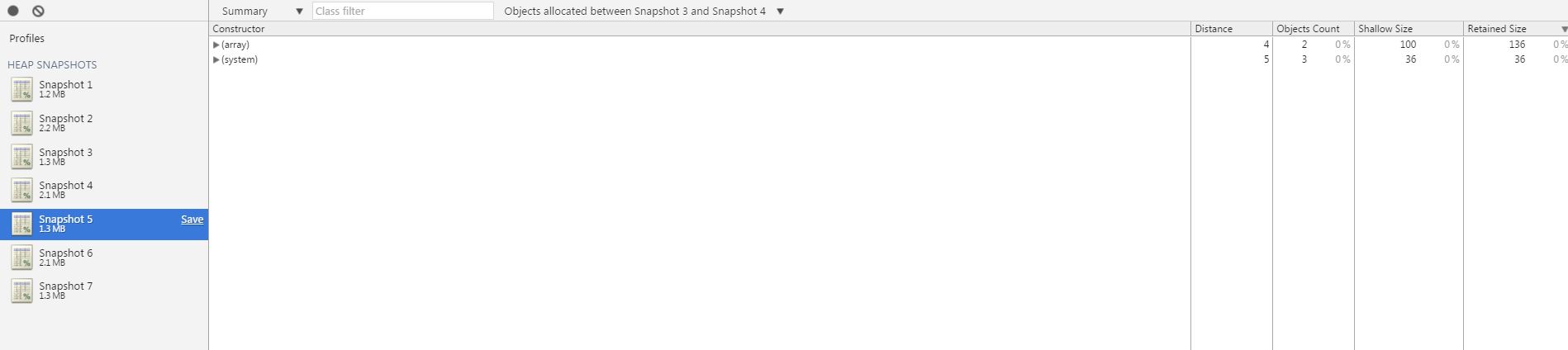

But wait, the browser internals makes us worry, we don’t want to stick our head in the sand and we want to make sure nothing is leaked. No problem, lets take a look at snapshot #7 and there compare objects that were allocated between #3 and #4:

We see nothing. No memory size increase, no allocated objects, internal or not. That means that whatever happened in #3-#4 was completely removed, meaning we don’t have any leaks.

Do you see the difference? Using 7 snapshots we validated that we don’t have linear memory leak and our application in an healthy mode. But if we would’ve used only 3 snapshots, we could’ve been wasting our time chasing down retainers just to find the that it’s really OK for the singleton and the internal JS interfaces to be kept in memory.

What about one-time leaks?

You are right to think that only the 3 snapshot technique will catch a leak that happens only once between snapshots #1 – #2. Unfortunately i don’t have a better advice than going and checking every single retainer, understanding what it does and than deciding if it’s a leak or by design. My only advice is to be smart about it, if you see that in the first run your memory jumps to unreasonable numbers (unreasonable depends on the application and the devices running it), you’re definitely should take the time to look into it. But if the have an additional 100-200kb, or even 1mb that allocated only once and you’re not sure if they should, most of the current devices (of course with some exceptions) are strong enough to make you think twice if it’s worth your time.